THE CLINICAL UPDATE | SPRING 2021

Membership renewal for fiscal year | Upcoming events

|

Letter from our President, Amanda Lee, LCSW

At the time of writing this, on the day we commemorate the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr., admittedly, I find myself more distracted and uncertain than I imagine most of us hoped to be in the new year. We just exited an incredibly dismal year, 2020, which carries symbolic significance, but continue nonetheless to face unprecedented challenges to almost every aspect of our identities. I can almost smell the burn out, taste the saltiness (trickling over my cheeks) of unrelenting loss and grief, and feel the weight of trauma, historical, personal and vicarious, heaped upon our shoulders. There is so much at stake, and yet so much of it seems beyond our control. Undoubtedly, we are hearing echoes of the same sentiments from the clients we serve. As behavioral health professionals providing clinical services, regardless of the setting, we have been tasked to manage and heal the effects of a global pandemic, health disparities, structural racism and political contention. The work we do with each individual, family, couple, group, and community are a direct and focused response to the great need before us, but we also need to ensure that we are taking care of ourselves professionally, or there will be no one left to do this vital work.

At the time of writing this, on the day we commemorate the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr., admittedly, I find myself more distracted and uncertain than I imagine most of us hoped to be in the new year. We just exited an incredibly dismal year, 2020, which carries symbolic significance, but continue nonetheless to face unprecedented challenges to almost every aspect of our identities. I can almost smell the burn out, taste the saltiness (trickling over my cheeks) of unrelenting loss and grief, and feel the weight of trauma, historical, personal and vicarious, heaped upon our shoulders. There is so much at stake, and yet so much of it seems beyond our control. Undoubtedly, we are hearing echoes of the same sentiments from the clients we serve. As behavioral health professionals providing clinical services, regardless of the setting, we have been tasked to manage and heal the effects of a global pandemic, health disparities, structural racism and political contention. The work we do with each individual, family, couple, group, and community are a direct and focused response to the great need before us, but we also need to ensure that we are taking care of ourselves professionally, or there will be no one left to do this vital work.

California Society for Clinical Social Work (CSCSW), its Board of Directors and I am committed to doing everything we can to meet the specific needs of our members during not only this critical time, but also in the better days we all dream will come sooner than not. We draw upon inspiration from the founders of CSCSW who were instrumental in establishing our license, the LCSW, in California in 1965 for clinical social workers and from our members who advocated in 1975 for parity with other mental health professionals, such as psychiatrists and psychologists, so that LCSWs could bill insurance companies and become private practitioners. In times of adversity, we can fold or flourish. CSCSW has grown, adapted and critically examined our infrastructure with the aim of promoting greater access, strength in diversity and innovation in practice. We are grateful for how well received the changes to our programming and approach have been, but we are also acutely aware that our work has just begun and are excited about the direction we are headed together.

Our profession emphasizes the importance of self-care, and a critical component of self-care is how we value what we contribute to society and is it reflected in what we are paid. LCSWs may have parity when it comes to the ability to bill insurance, but not in what is ultimately reimbursed. CSCSW is the only organization in California that has as its mission the advancement and promotion of the profession and practice of clinical social work. CSCSW’s Advocacy Committee is actively seeking to engage members in addressing legislation that directly impacts their professional well-being. The Board of Directors is working collaboratively with the members of the Advocacy Committee on the recruitment of a part-time lobbyist dedicated to advocate for matters relevant to clinical social workers such as equitable pay for essential work and title protection. Social justice is a core value of the social work profession that we embrace openly for the clients we serve, but sometimes less so when it comes to our own professional needs. To practice professional self-advocacy is to practice an integral aspect of self-care. Please look for a survey from the Advocacy Committee inviting your input on what matters most to you.

Investing in our development as a clinical practitioner is a commitment not only to the core value of competence, but also to our professional self-care. CSCSW’s Education Committee and District Coordinators have determinedly organized a wide offering of training opportunities through workshops and district meetings using a virtual format during the pandemic. One of CSCSW’s longstanding priorities has been to help its members easily fulfill their continuing education requirements through programming on clinical practice. For example, “The Art of Psychotherapy” workshop series presented by Dr. Wanda Jewell, has been extremely well-received and valued by new and seasoned clinicians alike. Many members have discovered new networks as a result of participating in these learning forums, and are able to connect to, build and be a part of a professional community, overcoming the physical isolation that social distancing demands of us.

The events of the summer reemphasized the presence of a similarly devastating pandemic, that of racism, bigotry and oppression, raging in parallel. We are not immune, even as social workers espoused to the core value of social justice. We have been called to bravely address our own privilege and part in (whether conscious or not) perpetuating systemic racism, and also to invest real time and effort in learning and applying the ways to promote racial justice for our clients, colleagues and communities. CSCSW’s Education Committee, in consultation with the Diversity, Equity and Transformation (DET) Committee, has planned several upcoming pertinent workshops such as “Incorporating Critical Race Theory in Clinical Social Work”, “Providing Clinical Services to African American/Black Men and Youth Who are Experiencing Traumatic Grief’, and “Equitable Supervision”. We are thrilled to have Nicole Vazquez, Dr. Allen Lipscomb and Dr. Wendy Ashley, respectively, bringing their subject matter expertise to each presentation. The DET Committee also continues to offer a consultation/support group called “Real Talk” for practitioners who identify as Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) to provide an opportunity for networking, building solidarity, exploring intersectionality and decolonizing our clinical practice. This is ongoing work that is demanding, and that requires much more than attending one training, reading one book, or participating in one protest. This work is transformative for you personally and professionally and will require support.

CSCSW is there to provide you with the support you need. The Member Benefits Committee continues to cultivate the extensive list of benefits you receive as a member of CSCSW. Many of the benefits have already been mentioned above, but it is worth stating again that members receive FREE CEUs for attending District Meetings featuring a variety of clinical topics. In addition, as a member, we hope that you take advantage of the other tools that will help you to advance in your practice, including, the Mentorship Program, BBS Liaison, Ethical Consultations, Listserv, Supervisor List, Therapist Finder and Job Marketplace. CSCSW also continues to offer a consultation/support group to those providing services through telehealth and other networking opportunities arranged by Districts. We greatly appreciate all our members’ contributions to make this a rich and diverse community of clinical practitioners. Consider inviting your colleagues to invest in their own professional wellbeing by joining CSCSW today.

In closing, there is still so much more to come. The Board of Directors have been actively recruiting applicants to join the board during a special election period so that we have the resources to efficiently respond to your needs as members. We will have another board recruitment period towards the end of the fiscal year in June, so if you missed the opportunity to apply as a candidate this time, please consider putting your name in the hat the next time around. Everyone likes a makeover! Keep an eye out for the unveiling of our CSCSW website’s redesign and relaunch coming soon. We hope that the revamped platform will better meet the needs of our members. Finally, in an effort to promote transparency, the Board of Directors plans to both host a townhall event and establish an open session at the beginning of each board meeting so that CSCSW members can attend and provide their input and ask questions. More to come in a future announcement on these plans. I have greatly enjoyed getting to know some of you in the various virtual settings and look forward to getting to know many more of you in the days to come. I appreciate the opportunity to serve as your president and the time you took to read this. Be well.

Amanda Lee is a LCSW and has a MSW with a concentration in Gerontology. She has over 16 years of experience practicing social work in a variety of settings and roles within the health and human services field, including, within adult and older adult outpatient and inpatient behavioral health, home-based intensive treatment, and PACE, and also overseeing county-contracted programs as an administrator, providing clinical supervision to license-eligible BBS registrants and teaching in social work education. She has also been registered and practiced social work abroad in New Zealand and was instrumental in the development of a sub-acute treatment and rehabilitation team for older adults with severe and persistent mental illness. She has extensive experience working with cultural minorities, such as Asian and Pacficic Iislander immigrants and refugees and individuals who identify as LGBT. She is also passionate about health care integration, and values a whole-person approach to wellness and recovery. She teaches as a lecturer and oversees the field education component of the School of Social Work at San Diego State University. Amanda currently serves as the President of the California Society for Clinical Social Work (CSCSW) and chairs the Diversity, Equity and Transformation (DET) Committee. She lives in San Diego, loves animals (particularly her kitty and pittie), Disneyland, and bowling.

BBS Updates

By Caitlyn Conley, MSW

In attendance of the CA BBS meeting on 11/6/2020, the BBS has reported the following updates regarding clinical social work practice:

- As of January 1, 2021, fees will be increased for all mental health professionals for both initial licensure and renewal. Please click here to see the changes in fees.

- Pearson VUE continues to offer in-person exams for licensure. Please be aware of their COVID-19 practices and know that space may be limited at certain testing sites. Click here for more information from Pearson VUE's website.

- Telehealth across state lines in the time of this pandemic has created many questions about legality of practice. The BBS continues to hold meetings regarding Telehealth practice, please go to the BBS website to watch the most recent Webcast from their 01/22/2021 meeting regarding any pertinent updates for Telehealth. Please click here for an info guide on best practices.

The next scheduled BBS meeting is on 03/05/2021.

Caitlyn Conley, MSW is currently the Advocacy Committee Chair and Secretary on Board of Directors for CSCSW.

Getting unstuck: The Promise of Psychedelic Assisted Therapy

By Andrew Penn, MS, PMHNP (Psychiatric Mental Health Nurse Practitioner)

I was honored to present about psychedelic assisted psychotherapy to your Society last year. Below, I’m going to reiterate my key points, focusing on the role of psychotherapy in this emerging treatment.

I was honored to present about psychedelic assisted psychotherapy to your Society last year. Below, I’m going to reiterate my key points, focusing on the role of psychotherapy in this emerging treatment.

Psychedelic assisted therapy, in the form of current studies into the effectiveness of psilocybin (the active ingredient in so called “magic mushrooms”) for the treatment of depression, and the use of MDMA (3,4 methylenedioxymethamphetamine) in the treatment of PTSD, represent the renaissance of clinical studies of psychedelics in the 1950’s and 1960’s. While the reputation of these drugs was besmirched by the zealotry of Timothy Leary and others and their use in the youth culture of the time, prior to this, drugs such as LSD and psilocybin were being used to treat depression and alcohol dependency. These studies were effectively ended by the Controlled Substance Act of 1970 and most therapists now were only trained in these drugs as substances of abuse.

Currently psilocybin treatment of depression was granted breakthrough status by the FDA, and is being advanced by two separate sponsors in phase 2/3 trials. MDMA assisted therapy for PTSD is part-way through phase 3 clinical trials and was also given breakthrough status from the FDA in 2017 (Feduccia et al 2018). I have worked as a study therapist in the MDMA-assisted trial for PTSD and am training to work on a psilocybin-assisted trial for depression.

This therapy is typically delivered by two specially trained therapists in a safe, comfortable, living room like environment (probably not unlike your therapy office!), after several hours of preparatory therapy in the days before. The subject is encouraged to lie down on a couch, don eyeshades and headphones over which a preselected program of music is played. The patient is never left alone, as the two therapists stay until the drug is worn off and the patient is safely going home with a trusted person. All of these measures provide for safety and encourage the subject to direct their attention inward. After the drug/therapy session, there are several sessions of integration therapy with the same clinicians in the days and weeks that follow (Johnson et al 2008).

It is important to understand that, while the psychedelic drugs under study have garnered a lot of sensational headlines (“Party drug treats PTSD!”), the purpose of this model is really to catalyze the psychotherapy.

As we clinicians know, in the current split model of care, a prescribing clinician (usually a PMHNP or physician) prescribes medication and provides brief, supportive therapy, while another clinician (a therapist), provides psychotherapy. While there may be a nonspecific promotion of the therapy via the medication, the drug is not chosen to specifically enhance psychotherapy. In psychedelic-assisted therapy, the drugs used are specifically chosen to target key barriers in the treatment of those disease states (in PTSD, it is excessive fear and avoidance; in depression, it is rumination and difficulty with shifting out of the depressed state).

Outcomes have been impressive. In phase 2 studies of MDMA assisted therapy, At the end of the treatment, 54% of subjects treated with MDMA no longer could be diagnosed with PTSD, vs 23% of placebo treated subjects (Mithoefer et al., 2019). Side effects included mild elevations in blood pressure and heart rate, loss of appetite, insomnia, and transient anxiety, all of which were able to be managed without hospitalization or rescue medication. The study sponsor, the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelics Studies is currently conducting an interim analysis of the phase 3 data and hopes to apply for FDA approval in 2022-2023 if the results are favorable.

Psilocybin is being explored as a treatment for depression, following studies at Johns Hopkins and NYU examining the use of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for persons facing emotional distress related to life-threatening illness, demonstrated dramatic and enduring benefits for most subjects (Griffiths et al 2016, Ross et al 2016). Similar to MDMA, side effects were transient and included hypertension, tachycardia, and transient anxiety/paranoia that could be managed with reassurance from the study therapists. The two sponsors of these studies, Usona Institute, and Compass Pathways, hope to apply to the FDA for approval in the next 2-4 years.

Depression, substance dependency, eating disorders, PTSD, OCD, and many other psychiatric conditions can be seen as conditions in which the patient has difficulty changing. This low-change, rigid state has been described by pioneering psychedelic neuroscientist Robin Carhart-Harris and colleagues (2014) as a state of low entropy. His research into neuroimaging of people undergoing psychedelic experiences has found that the brain under a psychedelic often operates in a more unpredictable, more entropic state. It appears that the brain “resets” after the psychedelic state in a way that is more flexible and open to change. This is what I call “getting unstuck” in therapy. This model of psychological health being marked by mental and emotional flexibility is similar to that which is taught in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, a model that is being adapted for psychedelic psychotherapy (Watts et al 2020).

Psychotherapists, especially those who work in a depth model, are familiar with the idea of taking a long voyage with their clients (Hill, 2013). Jung described the archetype of “the hero’s journey” which has been the framework of countless books and films, but could easily be thought of as a template for any deep psychotherapeutic work. In this model, the hero (in this case, the client), leaves the world has he or she has known it, and passes through a threshold. For many of our patients, this threshold is the entry into psychotherapy, but could be a significant life event like a trauma or a loss. Past that threshold, they are asked to confront demons and face obstacles. At the most intense, there can be a fear of obliteration as the hero releases parts of themselves that they once thought of as central parts of their identity, but may in fact be holding them back. The hero often needs the help of allies, such as the therapist, in shedding these past traumas and schemas about themselves. Sometimes this process is humorously absurd as we realize how we have been working against ourselves all along. We develop compassion for ourselves and even for those who hurt us. And when the journey is complete, we emerge back into our daily lives, subtly but importantly and irreversibly changed. These changes may not be immediately evident to the people around the hero, but given time, the trajectory of their life will be changed.

The process described above, is similar to that which I have witnessed in my research work with subjects undergoing psychedelic psychotherapy, only that it is accelerated by the psychedelic. In the psychedelic state, patients often find themselves struggling with demons from the past, which can elicit strong emotional reactions. However, supported by the container of the therapeutic relationship and in the safe space of the therapeutic room, these demons can be faced and the relationship with them can be changed. Through integration therapy that follows the drug session, subjects can begin to shift their internal relationship with these parts of themselves for the better. A framework of Internal Family Systems has also been used in psychedelic sessions to help patients learn to understand and embrace the different facets of self that may emerge during psychedelic sessions.

These treatments will need to be delivered by specially trained therapists in order to be used safely and effectively. It is likely that the FDA will specify the training required of psychedelic psychotherapists, but it is unclear at this moment what those requirements will be. Many different educational organizations have begun to offer training in psychedelic therapies, such as the California Institute for Integral Studies Center for Psychedelic Therapies and Research, of which I am a graduate. While these programs offer a dynamic and stimulating program of study and the opportunity to learn from some of the most preeminent thinkers and researchers in this field, it is important that no one knows if these programs will satisfy future regulatory requirements for psychedelic therapists. My advice to those who are interested is to read and learn all you can so that you can be prepared to at least answer questions that will undoubtedly be coming from your patients. I encourage an open, receptive mind as we navigate what is arguably one of the most interesting moments in clinical mental health in some time.

- Carhart-Harris RL, et al. The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:20.

- Feduccia AA, Holland J, Mithoefer MC. Progress and promise for the MDMA drug development program. Psychopharmacol. 2018;235, 561–571.

- Griffiths RR, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181-1197.

- Hill SJ (2013) Confrontation with the Uncincious: Jungian Depth Psychology and Psychedelic Experience, Muswell Press, London

- Johnson M, et al. Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(6):603-620.

- Mithoefer M, Feduccia A, Jerome L. et al. MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of PTSD: Study design and rationale for phase 3 trials based on pooled analysis of six phase 2 randomized controlled trials. Psychopharmacol. 2019; 236(9), 2735-2745.

- Ross S, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165-1180.

- Watts R, Luoma JB. The use of the psychological flexibility model to support psychedelic assisted therapy. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2020;15:92-102.

Andrew Penn, MS, PMHNP is a UC San Francisco trained psychiatric nurse practitioner. He serves as an associate clinical professor in the UCSF School of Nursing and practices at the San Francisco VA where he works with NP residents and students. He completed extensive training in psychedelic assisted therapy and has worked as a study therapist on a MDMA-assisted therapy protocol for PTSD. He is a nationally-recognized speaker on psychedelic assisted therapy and cannabinoids in psychiatry and can be found at andrewpennnp.com.

Using Critical Race Theory to Improve Social Work Practice

Sharon Chun Wetterau, LCSW, California State University, Dominguez Hills | Department of Social Work

In light of the state sponsored deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd and other people of color murdered by on-going police brutality, the notion of race and its impact on Black, Brown, and indigenous people continue to capture the nation’s attention. These events serve as a “call to action” for social workers to look critically at the impact of systemic oppression on marginalized communities. Critical Race Theory is a useful and dynamic theoretical framework that has been utilized in social work to assist practitioners to look critically at themselves and at the structural inequities impacting the well-being of clients and their communities.

In light of the state sponsored deaths of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd and other people of color murdered by on-going police brutality, the notion of race and its impact on Black, Brown, and indigenous people continue to capture the nation’s attention. These events serve as a “call to action” for social workers to look critically at the impact of systemic oppression on marginalized communities. Critical Race Theory is a useful and dynamic theoretical framework that has been utilized in social work to assist practitioners to look critically at themselves and at the structural inequities impacting the well-being of clients and their communities.

Critical Race Theory (CRT) is a fluid, bi-directional post-modern approach that originated in legal scholarship in the 1970s and 1980s following the post-Civil Rights era (Ortiz et al, 2010). Despite the passage of Civil Rights legislation, CRT scholars have argued that people of color remain at the margins and that racism has become so normalized that it had become “ordinary” in everyday life (Abrams & Moio, 2009, Razack & Jeffery, 2002). They posit that race is a social construction where the status of varying racial groups could be changed over time in order to serve the economic, political and social needs of those in power, namely Whites. In addition, racial groups are portrayed by the dominant group as homogenized “others” who have “fixed” or stereotyped characteristics on which marginalization can be justified, whether consciously or unconsciously (Solórzano & Yosso, 2001). Critical race theorists have critiqued liberalism and its focus on changing the individual as opposed to societal structures leading to one’s problems (Daniel, 2008).

Other Important Critical Race Theory Tenants Relevant to Social Work

- Intersectionality: the recognition that one’s race, gender, class, sexual orientation, perceived ability, immigration, religion, etc. in different contexts and has bearing on one’s social, political, and economic status. An undocumented Latino HIV+ adolescent in the Mid-West may have less access to treatment and services than a lesbian HIV+ African American woman in a large urban area (Abrams and Moio et al, 2009)

- Voices of the Other: the purposeful elicitation of narratives of marginalized groups and individuals to serve as counter-narratives to dominant narratives and the incorporation of these counter-narratives to transform oppressive structures and practices (Ortiz et al, 2010)

- Power and Privilege: the recognition that power and privilege are differentially located according to one’s race, class, gender, sexual orientation, perceived abilities, immigration status, etc. This power and privilege differential is often masked and rendered “invisible” by and within dominant groups, whereas those without power and privilege are often aware of this differential. The raising of awareness and the further examination of one’s privileges, including White privilege, are critical (Abrams & Gibson, 2007). Also critical is analyzing how privilege has lead to the systematic oppression of groups and that all forms of oppression impact dominant groups, not just subordinate groups (Daniel, 2008; Abrams & Gibson, 2007; McIntosh, 1989).

- Microaggressions: Sue at al (2007) describe racial microaggressions as “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of color” (p. 271). Examples of microaggressions include: assigning intelligence or criminality to a person of color based on their race; opening a door for a person in a wheelchair; telling a lesbian that she “looks straight;” and the overabundance of liquor stores in communities of color and immigrant communities. Microaggressions disrupt the client-practitioner relationship and relegates clients to a socially inferior position.

- Positionality & Social Location: One holds power and privilege based on intersecting social identities in a variety of contexts. While an affluent African American woman may hold class privilege in the United States, she may also be subjected to microaggressions and discrimination based on her race. In examining one’s social location, it is also critical to examine the wider socio-economic structures producing the client’s individual “troubles” which impact their social location (Heron, 2005).

- Critical Reflexivity: Critical reflexivity involves careful and critical examination of oneself and others in terms of social location, power, and privilege (Heron, 2005). It takes into consideration the impact of existing social stratification and inequities that impact their own and their client’s social location. For instance, because a social worker is always in the position of power when working with a client, they must consider how to use this positionality in a way that maximizes client outcomes.

Case Example: Application of CRT

Consider the following case: A child welfare social worker is called out to the home of a Hmong family who immigrated from Laos to the United States in the past two years. The family lives in the suburb of a small U.S. city. The allegation involves neglect by the parents toward their five children, ages 2 months through 16, and there is a concern about the family’s sixteen year-old daughter who is pregnant. When the social worker arrives at the home, she follows her agency’s protocol and looks through the cabinets and refrigerator to find very little, if any, food in the refrigerator and cupboards. When the social worker asks about how the family is doing, the father tells her that his daughter cannot stay in his home and will need to find another place to live.

What assumptions might a social worker make about this family? Some social workers may conclude that this family does not have adequate resources at home to feed and care for their family. They may also be concerned that the sixteen year-old daughter is being mistreated and “kicked out” of the family unit due to her pregnancy.

A social worker informed by Critical Race Theory could come to a different conclusion and recommendations for this family by:

- Taking an unassuming stance, using critical reflexivity. This could include having the social worker openly acknowledge the different backgrounds from which they both come and inviting clients to clarify and disagree with the worker if s/he shares an observation with which they disagree. Critical reflexivity might also include the social worker readjusting the assessment and recommendations based on client input.

- Recognizing the privileges that the social worker brings to the relationship and examining underlying biases that the social worker might have about the clients based on their social identities, social location, and past and current experiences of oppression

- Minimizing the use of microaggressions (e.g. not assuming the family does not know how to survive in this country)

- Eliciting and giving credence to the “lived experiences” of this family by asking the clients to share their narrative about their life in Laos, the trauma that they may have witnessed, the immigration and adjustment process to this country, their experiences with employment and education, the roles assumed by this family while in Laos and in the context of their current experiences as immigrants

- Inquiring about how the members of the family care for one another, the use and expression of spirituality or religion, degree of connectedness and quality of social support within and outside the Hmong community, cultural resources, and strengths

- Exploring the cultural and family’s view of pregnancy, including rituals or traditions surrounding the care of females who are pregnant

- Considering the social location of this family given the intersection of their multiple identities and varying experiences of oppression in this country. For instance, if the parents are exploited in low-wage jobs, they may need assistance getting connected to TANF.

- Reviewing of agency policies to ensure that the civil rights of clients are protected. Policies related to the detention of children should be flexible and consider a multitude of variables within family contexts.

In this case, the allegations of neglect were unfounded, and the family remained intact, except for the teenage daughter, but only temporarily. The social worker in this case assumed that she knew nothing about Hmong families and took the time to listen and learn about how meals were provided meals and the kinds of foods they ate (almost all of their food was grown or raised in the family’s backyard, including chickens). The worker also learned that in this traditional Hmong home, a pregnant woman must live in another place for thirty days, but after that time, could return home. The daughter’s age had nothing to do with her needing to leave the house.

Contextually-Competent Practice

Thus, when working with families utilizing a CRT framework, it is important to utilize assessments, interventions, and evaluations in a contextually competent way. This contextual model challenges the existing cultural competence model which promotes the understanding and acceptance of the differences between racial, ethnic, and other marginalized groups, but tends to ignore the structural factors that lead to their marginalization (Ortiz & Jani, 2010; Abrams & Moio, 2009). Each child, adolescent, and adult within a family system must be carefully assessed within their unique historical, socio-economic-political contexts and their intersecting identities and experiences with structural oppression.

This article was originally published in the Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults (CAYA) Newsletter in the Fall/Winter of 2015. This article has been reprinted with permission from the author.

Chun Wetterau, S. (2015). Critical race theory to improve practice. In Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults CAYA Newsletter, National Association of Social Workers blog. https://www.socialworkers.org/assets/secured/documents/sectors/caya/newsletters/2015-%20CAYA%20Fall%20Issue.pdf.

Sharon Chun Wetterau, LCSW, is Assistant Field Director at California State University, Dominguez Hills Department of Social Work, a program founded upon Critical Race Theory. She can be reached via email at swetterau@csudh.edu. Special thanks to Professors Cher-Teng Yang and Yeng Xiong, from California State University, Fresno, who served as consultants on the case presented.

Codependency Has Failed. What Comes Next?

by Robert Weiss PhD, LCSW

Not long ago, I introduced the concept of prodependence to the therapeutic community. I developed this new way of looking at, thinking about, and treating caregiving loved ones of addicts and other struggling individuals because I have never felt comfortable applying the codependency model to this population. Codependency’s emphasis on pathologies in the caregiving loved one, rather than on the trauma of living with an active addict or a similarly troubled person (a severely mentally ill person, for instance), felt misguided. Finding “something wrong” with the non-addicted loved one, in my mind, ignored the overarching human need for intimate attachment.

Based on those misgivings, I researched codependency for both my PhD dissertation and a new book (Prodependence). After reading countless books and articles about codependency and talking to hundreds of colleagues at every level of addiction treatment and family therapy, I reached the following conclusions:

- Over the years, there have been so many versions and adaptations of the codependency model that the intent of Claudia Black, Mellody Beattie, and others who introduced the concept bears little to no resemblance to the “codependency treatment” clinicians now provide to loved ones of addicts and others who struggle.

- Despite the ongoing lack of clarity about what codependency is and how to best treat it, many (perhaps most) addiction and family clinicians automatically categorize caregiving loved ones of addicts and similarly struggling individuals as codependent – a label that often feels blaming and shaming to said loved ones. They think, I’m not the one with the addiction (or mental illness), so why are you focusing on me and telling me that I’m the one who needs to change?

- In nearly all of the adaptations of codependency treatment, caregiving loved ones of addicts and similarly troubled people are asked to question their motivations and life histories so they can identify why they are in a dysfunctional relationship, why they feel a need to care for an active addict, and what they need to change in their own lives.

- However it is practiced, codependency treatment causes caregiving loved ones to feel more pathologized than understood. And because of this, loved ones of addicts and other struggling people often walk away from therapy before clinicians can help them.

This knowledge led me to formulate a new model for working with caregiving loved ones of addicts and other struggling people. That model is prodependence. Using the prodependence model, clinicians do not attempt to find issues with caregiving loved ones. Instead, in the early stages of treatment, clinicians recognize that loved ones are in the midst of a crisis that is not of their own making and treat them accordingly by validating their emotional experience and helping them set healthy boundaries and make better in-the-moment decisions. In short, the clinician’s job, using the prodependence model, is to acknowledge the emotional trauma and dysfunction that occurs when living with an addict, and to address that in the least blaming/shaming way possible.

The codependence model might push a therapist to say:

It seems like you are enabling your husband’s drinking and making things worse rather than better. I wonder what motivates you to do that? It seems like you are trying to control his decision making and actions. This is likely a trauma-related response. Let’s look at your past to see what’s causing you to be enabling rather than helpful to your husband.

In the same situation, clinicians using the new prodependence model might say:

I am impressed with the ways you work to prevent your husband from drinking and driving. How wise to bring alcohol to him so he can drink at home and avoid another arrest or, worse still, an accident that might be fatal to him or an innocent bystander. That said, he’s still drinking, so let’s try to find some ways you can effectively help him address that issue.

I ask you, which statement is likely to push the client away, and which statement is likely to foster a productive therapeutic alliance?

Interestingly, at the end of the day, prodependence recommends and implements many of the same therapeutic action steps that we see with most forms of codependency treatment – resolving immediate crises, setting and maintaining healthy boundaries, engaging in self-care, and developing more effective ways to respond to and intervene on the active addiction. But prodependence does this work without causing clients to feel as if they are part of the problem.

Thus, the most obvious difference between prodependence and codependence lies in how we frame the problem. The following chart delineates this difference by listing behavior traits commonly seen in loved ones of addicts using both codependent and prodependent language.

Robert Weiss PhD, LCSW is Chief Clinical Officer of Seeking Integrity LLC, a unified group of online and real-world communities helping people to heal from intimacy disorders like compulsive sexual behavior and related drug abuse. He led the development of Seeking Integrity’s residential treatment programming and serves on the treatment team. He is the author of ten books on sexuality, technology, and intimate relationships, including Sex Addiction 101, Out of the Doghouse, and Prodependence. His Sex, Love, and Addiction Podcast is currently in the Top 10 of US Addiction-Health Podcasts. Dr. Rob hosts a no-cost weekly Sex and Intimacy Q&A on Seeking Integrity’s self-help website, SexandRelationshipHealing.com (@SexandHealing). The Sex and Relationship Healing website provides free information for addicts, partners of addicts, and therapists dealing with sex addiction, porn addiction, and substance abuse issues. Dr. Rob can be contacted via Seeking Integrity.com and SexandRelationshipHealing.com. All his writing is available on Amazon, while he can also be found on Twitter (@RobWeissMSW), on LinkedIn (Robert Weiss LCSW), and on Facebook (Rob Weiss MSW).

Confusion for LCSWs: Vaccines, Telemental Health Coverage, and Office Safety (January, 2021)

Laura Groshong, LICSW, CSWA Director of Policy and Practice

I’ve received 10 requests to give a webinar on the ways that LICSWs can safely return to the office in the past couple months. That interest has started to include vaccines and the safe practices for seeing working in-person if the patient and/or the LICSW have been vaccinated. Then there have been questions about whether third party payers will cover telemental health. This article will offer the best available information on these topics at this moment in time.

I’ve received 10 requests to give a webinar on the ways that LICSWs can safely return to the office in the past couple months. That interest has started to include vaccines and the safe practices for seeing working in-person if the patient and/or the LICSW have been vaccinated. Then there have been questions about whether third party payers will cover telemental health. This article will offer the best available information on these topics at this moment in time.

Vaccine distribution has been unpredictable and the distribution system has been chaotic. As of this writing, many LICSWs have had to wait in line for hours in DC to receive the vaccine, making social distancing more difficult, and even painful for those with older joints. Other citizens, including LICSWs, continue to have doubts about the safety of the vaccine and resist having them.

Eventually those who want to be vaccinated will be and the issue of whether to return to office practice will become more imminent. That appears to be 4-6 months away in most areas (to find out active outbreak areas go to https://covidactnow.org/us/california-ca/?s=1566506). Vaccinations and “herd immunity” – 70% of all people in a given area vaccinated or having had COVID – are the two main external factors to consider for returning to the office. Also worth considering is whether to allow patients into your office who have not been or refuse to be vaccinated, a fraught area for some.

Most experts say that even if you have been vaccinated, it is important to continue the practices we have been using to not infect others, e.g., using masks, washing hands, disinfecting surfaces after each patient, staying 8-10 feet apart, etc. Seeing patients with masks on can have as many disadvantages as working by videoconferencing. There are no absolutes here. If you choose to go back to the office in the next 4-6 months, it is recommended that you use a HEPA filter, check the air filtration, have windows that can be opened, and follow all the above practices. I’ve heard from numerous colleagues who feel the meaning of their offices has changed from a safe physical and emotional environment to a potentially dangerous one. That is a huge loss.

Finally, the Public Health Emergency (PHE) that currently is the basis for 3rd party coverage of our services is scheduled to end on April 21, 2021, after many extensions. Many insurers, including Medicare are likely to stop covering videoconferencing when that happens; audio only has already been ended on January 23, 2021. CSWA is working hard to get Congress to pass legislation that will make coverage of psychotherapy through videoconferencing and audio only permanent. Stay tuned for more information on the bills that will accomplish this. Likewise, HIPAA relaxation of rules that require ¬¬¬¬¬¬¬¬¬¬the use of a video platform which provides a Business Associate Agreement (BAA), NOT Skype, Facetime, and others, which do not provide a BAA, will likely be removed when the PHE ends. Getting a new platform is not the hardest issue we face, but it is one to keep in mind.

In summary, there are many uncertainties in our practices at the moment and there is no quick fix for returning to the office. The CSWA Town Hall meetings, held every three weeks on Zoom, have provided a modicum of comfort for those who attend, knowing that there are many colleagues going through the same frustration, exhaustion, and anxiety that we are. We are all in this together and will get through this crisis together. Visit www.clinicalsocialworkassociation.org

For more information go to the Johns Hopkins dashboard at https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6

Laura Groshong, LICSW is a Licensed Independent Clinical Social Worker in Washington and has been in clinical practice for the past 43 years. She is also a Registered Lobbyist in Washington for five mental health organizations. She was on the Board of the Washington Coalition for Insurance Parity for 10 years, the organization that was instrumental in passage of mental health parity in Washington in 2005 and 2007, as well as the passage of rules implementing these laws in 2014. She is the Director of Policy and Practice and Government Relations for the Clinical Social Work Association nationally and through the Mental Health Liaison Group worked on passage of the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equality Act of 2008. She has written and lectured extensively on clinical and legislative issues around the country.

Film Review: Searching for Soul

Reviewed by: Megan Koraly, MSW, ASW, PPSC

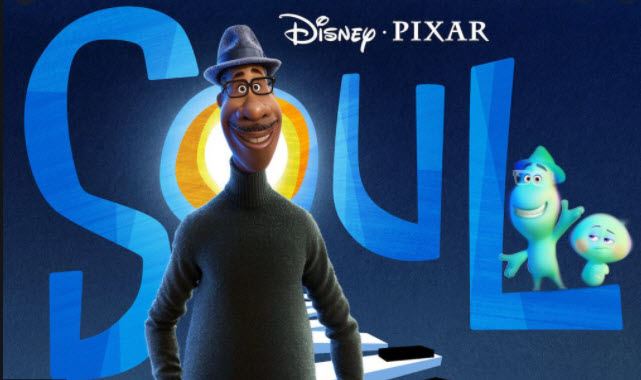

Disney’s Pixar is known for taking us on a ride through movies exploring what it means to be human. Whether it is learning the importance of friends, love and connection, such as in the movies Up and Toy Story to getting insight into our emotions in Inside Out (a favorite with child psychotherapist). Without exception, directors Pete Docter and Kemp Powers, dive exceptionally deep into the human experience in their latest feature film, Soul.

Photo property of Disney PIXAR

Soul stars a middle-school band teacher, Joe Gardner (voiced by the immensely talented Jaimie Foxx), who is on a mission to catch his big-break as a jazz musician in order to fulfill his life’s purpose. As life and movie plot lines go, our hopeful protagonist finds himself in an unfortunate mishap in the New York City streets. Joe’s soul is sent bouncing through mystical portals and landing on a conveyor belt sending him to a swirling kaleidoscope of souls headed for “The Great Beyond”. In disbelief and feeling he never really got to live, Joe scrambles to avoid his fated ending and drops into another soul world dubbed “The Great Before”. Here Joe learns that all these glowing, friendly casper-lookalikes are new souls that haven’t entered their physical earth bodies yet. In this soul training camp each soul earns their personality, unique traits, and most importantly finds their “spark” that grants them the coveted earth patch. Joe finds himself mentoring a new soul, named 22 (voiced by Tina Fey), who has failed to earn her spark and can’t see what the big deal of living is all about. Adventure ensues and 22 is swept up in the physical living world in all of its beauty, leaving the viewer with a few “ah-ha” moments. Through the eyes of Joe and 22 the viewer gains insight into what our true life’s purpose may be. Soul leaves you with a simple message based in the philosophy of mindfulness and awareness. In seeking our purpose, we must not forget to enjoy the real parts of living, like feeling the warm sun on our skin or the beauty of seeing the leaves on a tree. Soul shows us that purposeful living is done in those true moments of tuning in to the present moment right in front of us.

Megan Koraly, MSW, ASW, PPSC is an associate clinician in San Diego County with a passion and love for Social Work. Whether working with foster youth and families or in the school setting, she believes the true healing work is done through meaningful connections within the therapeutic relationship. Megan’s love for mindfulness has led her to pursue the path of becoming a Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction Certified Teacher.

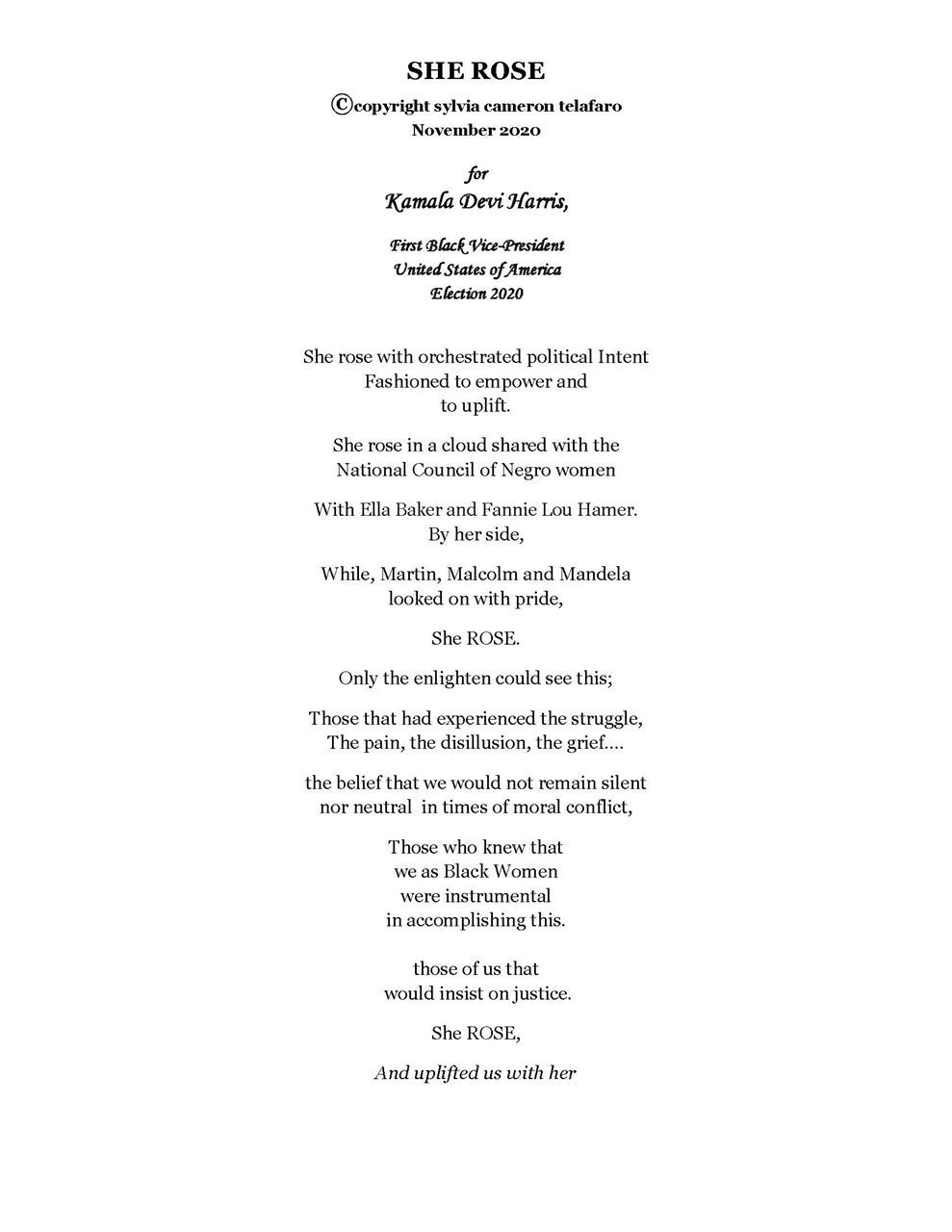

Poem: SHE ROSE

By: Sylvia Cameron Telafaro

Sylvia Cameron Telafaro is a poet, storyteller, and fiction writer. She is president of The African Americn Writers And Artist, Inc.San Diego an all volunteer Cultural Arts organization. She has had poems published in two Social Work Journals. Sylvia has been a part of the Administrative staff in the School of Social Work for 18 years.

About the Clinical Update

Editor: Janny Li, MSW, ASW

The Clinical Update publishes relevant, educational, and compelling content from clinicians on topics important to our members. Contributions and ideas for articles can be sent to Jannyli.msw@gmail.com -- please write "Newsletter" in the subject line.

Ad placement? Contact Donna Dietz, CSCSW Administrator - info@clinicalsocialworksociety.org

.png)